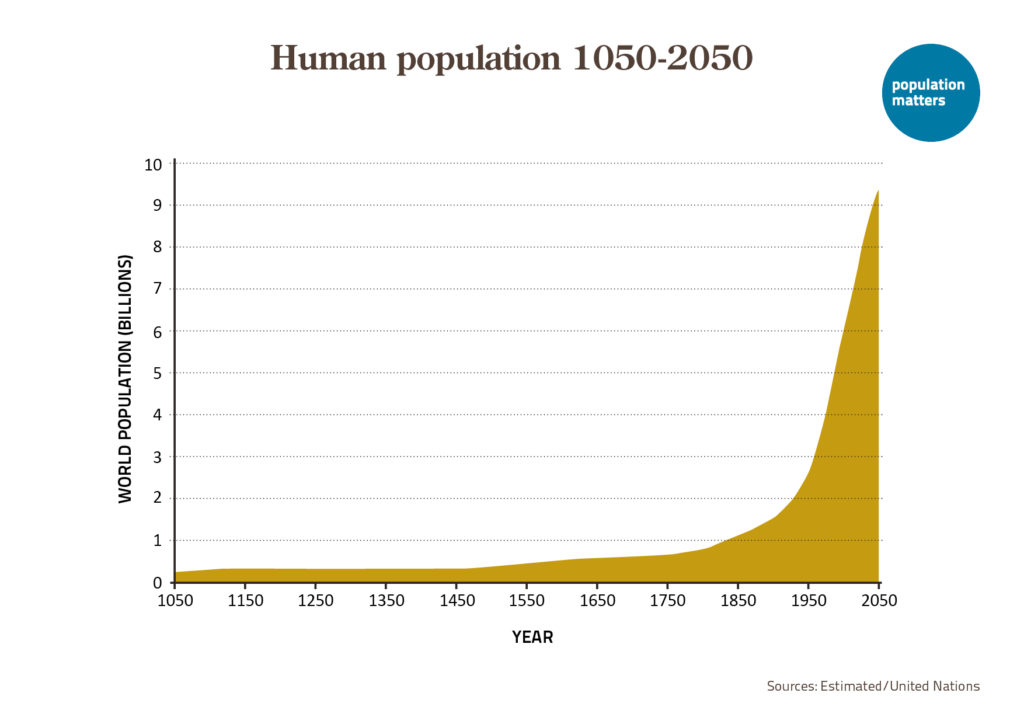

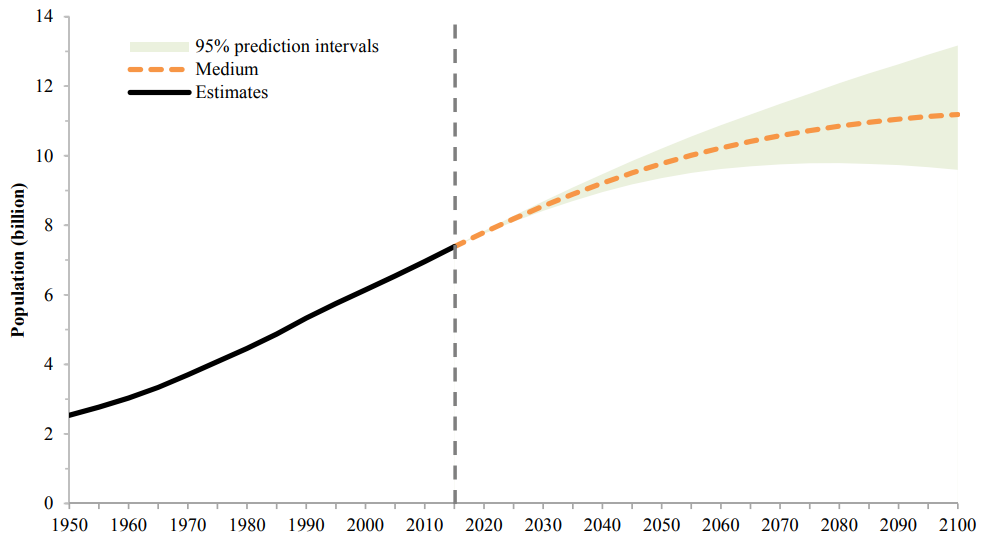

Are rich people with their private jets the main cause of climate change? Or are the hundreds of millions joining the middle class in China and India? Or maybe large families of poor farmers in the tropics deforesting to make room for low-productive agriculture? This blog questions the search for specific culprits, which is often ideologically motivated and risks undermining the difficult collective endeavor of finding a solution for current environmental issues.

by Giangiacomo Bravo

The champagne coupe of CO2 emissions

In recent years, regularly news has popped up in social and traditional media about the disproportional impact on climate change of rich people, usually presented as a shameless group of individuals happy to sacrifice the environment for their own welfare, or even the only real culprits of the climate crisis. The most well know representation of this argument is the so-called Oxfam “Champagne coupe” shown in Figure 1. According to Oxfam’s analysis, whose research was actually commissioned to the Stockholm Environment Institute, the richest 10% of the world population (about 800,000 people) is responsible for 50% of global greenhouse-gas (GHG) emissions, while the poorest 50% (about 4 billion people) only accounts for 8% of GHG emissions: a result that Oxfam labels as “shocking” and “obscene” [1].

The Oxfam report received praise but also criticism. What is important to understand is that similar estimations are difficult and can only be made under somewhat arbitrary assumptions. This said, comparable conclusions were also reached by an independent study published in the prestigious Nature Sustainability journal by the French economist Lucas Chancel [2]. Chancel shows that, between 1990 and 2019, the bottom 50% by income of the world population emitted, on average, 1.4 metric tonnes of CO2 per capita and year (11.5% of the total), the middle 40% emitted 6.1 tonnes (40.5%), and the top 10% emitted 28.7 tonnes (48%). In addition, Chancel argues that the top 1% emitted 101 tonnes per capita (16.9% total), showing how just 80 million individuals had an impact larger than half of the human population.

What about population growth?

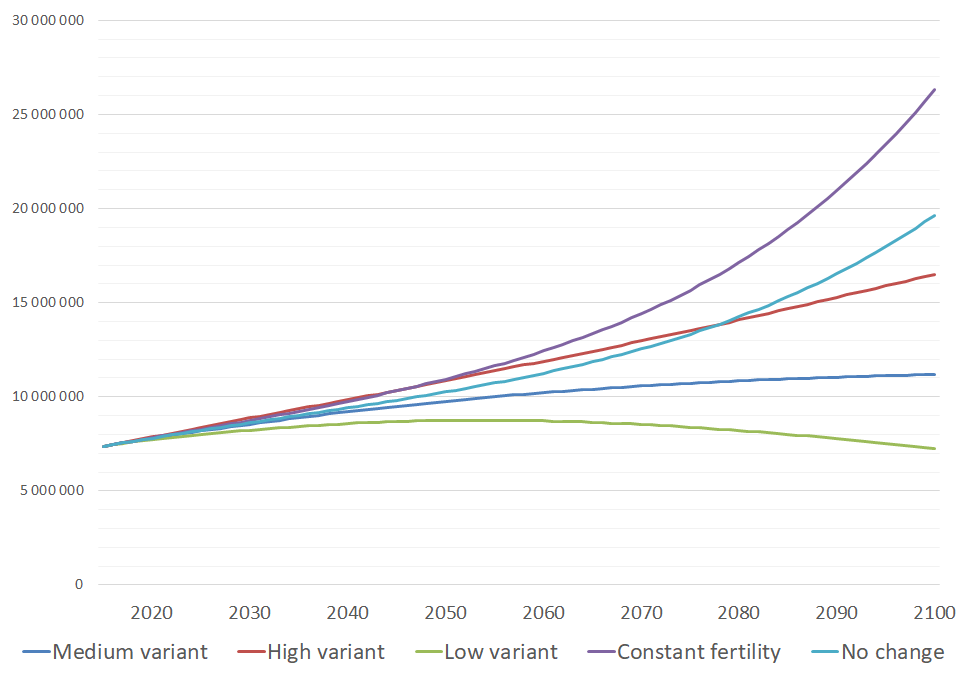

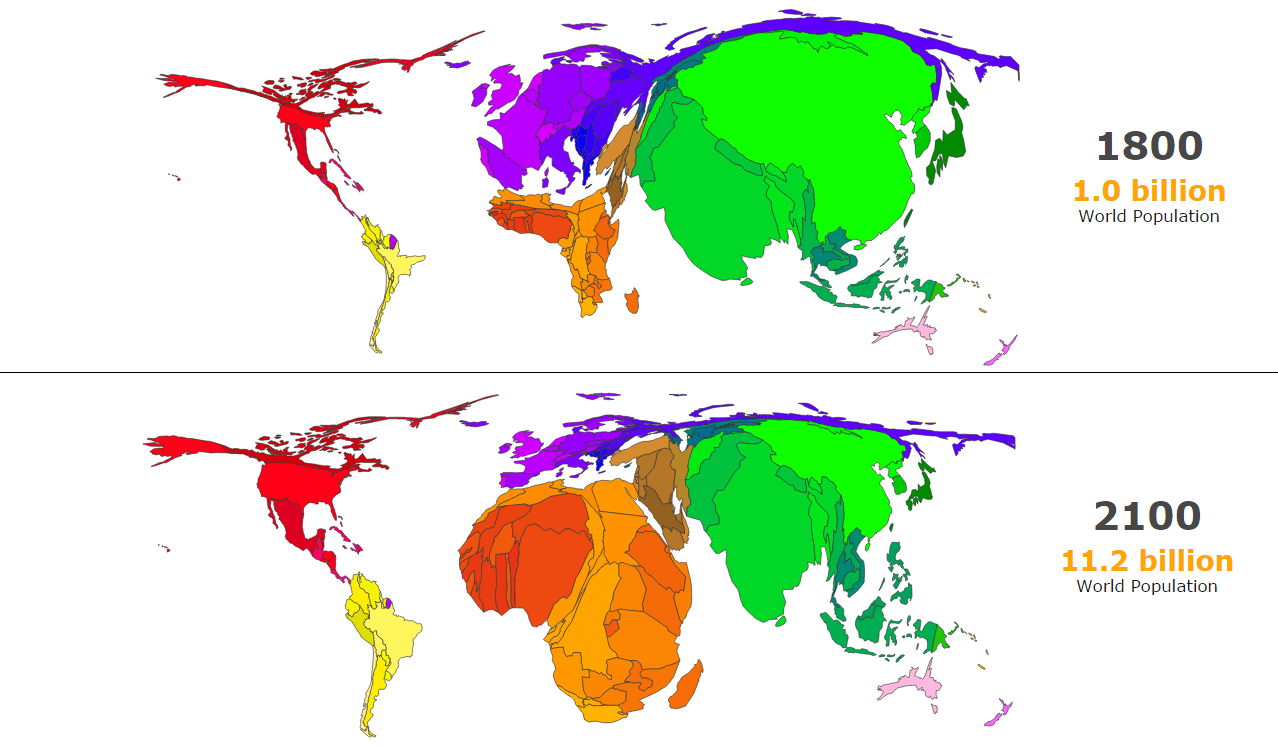

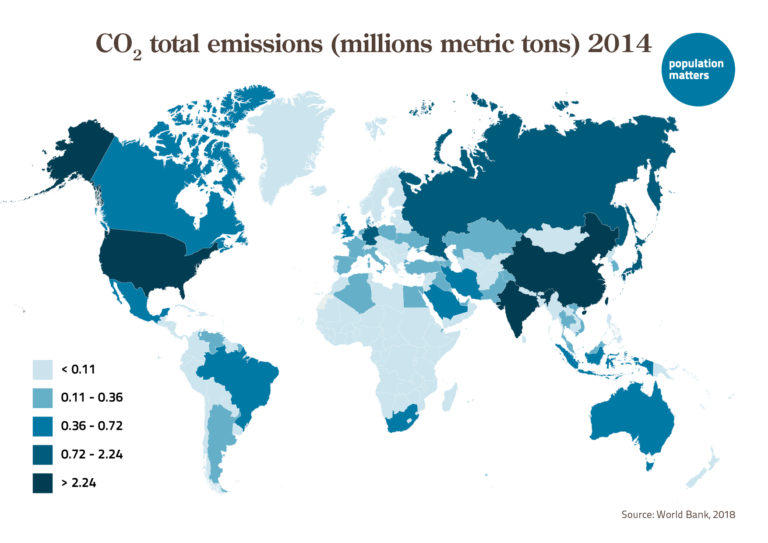

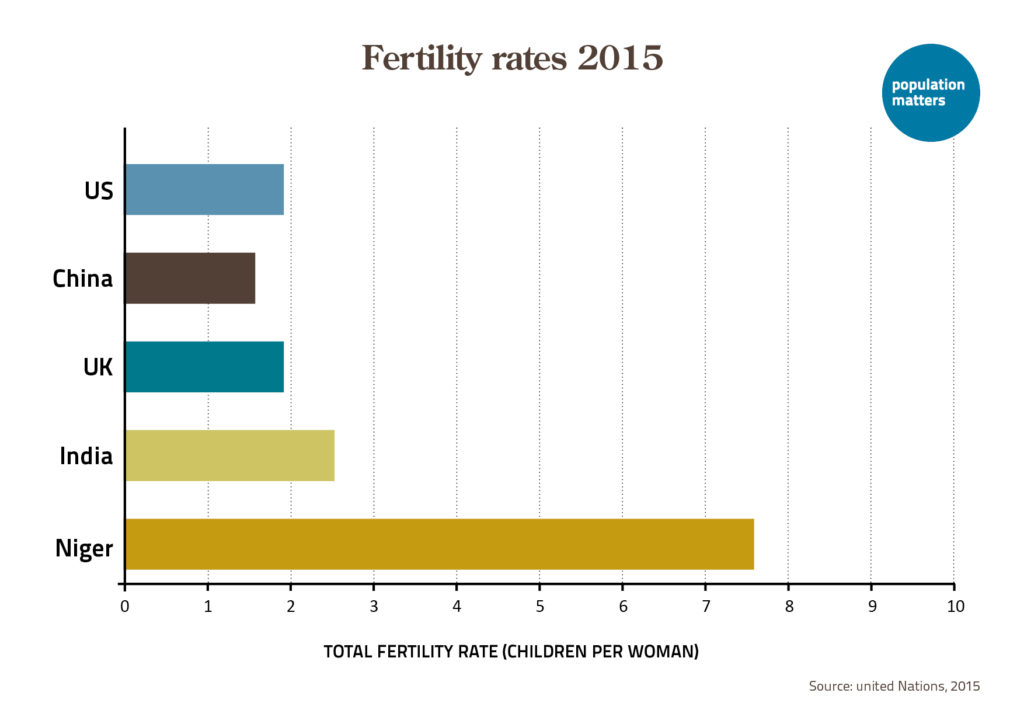

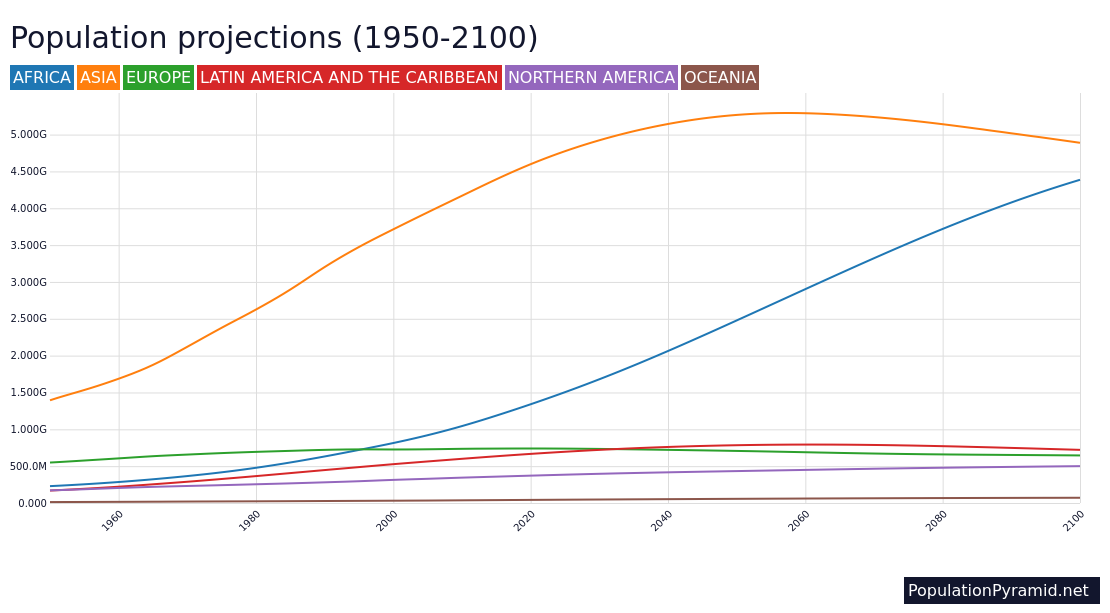

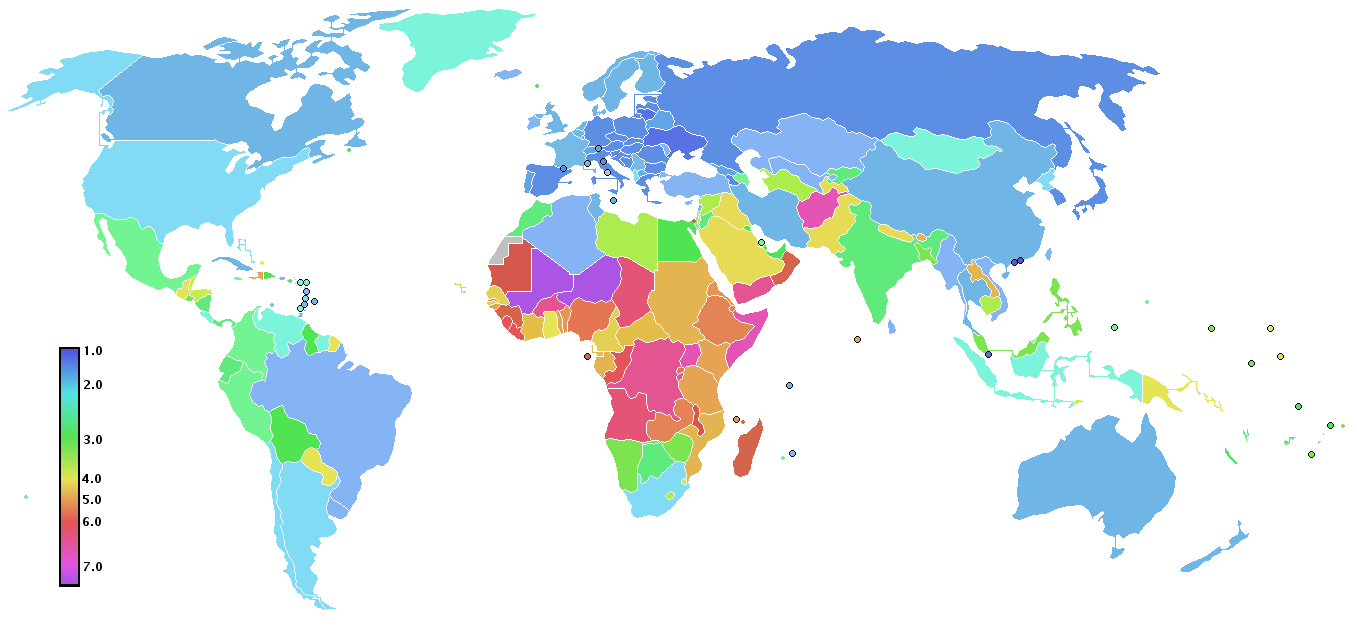

How to reconcile these findings with the outcome of other equally rigorous studies showing that population growth is a factor about as relevant as consumption growth in explaining the global increase in emissions [3, 4]? Here’s the problem: while most world countries have increased both their population and per capita emissions (depending on consumption and technology), this trend was not uniform among country groups between 1992 and 2019 (Fig. 2). Countries at the bottom and top of the income distribution kept their emissions relatively stable during this period. In the bottom, strong population growth was accompanied by a decline in average emissions per capita leading to an overall weak increase. In the rich countries, a small decline in per capita emissions was compensated by a small but not irrelevant population increase that is still occurring in most rich countries.

The actual driver of the emissions increases in the last 30 years was instead the enormous growth in both income and population that occurred in middle-income countries, with billions of people finding their way out of poverty and billions of new kids lucky enough to be born in families where food, shelter, health care, and education were no longer a mirage. The downside of this impressive achievement were the large amounts of CO2 that these countries emitted into the atmosphere, with the upper-middle group that is today the one producing most emissions in absolute terms, with per capita emissions that are approaching the levels of high-income countries (Tab. 1).

How does the growing impact of middle-income counties fit with the “Champagne coupe” picture? People moving out of poverty mainly switch from the dark-green bottom-50% group to the light-green middle-40% one in Figure 1. In a vast majority of cases, they are, however, not joining the ultra-rich group. Even more puzzling is that low-income countries, following the World Bank definition [5], only account for about 9% of global population, which means that a large share of Oxfam’s bottom-50% people were already in lower-middle income countries and never left the virtuous dark-green group while improving their standard of living.

To sum up, on the one hand we have a few millions of super rich people disproportionally producing CO2 emissions. On the other, the billions of people who escaped poverty or were born in middle-income countries in the last decades also have had a huge impact on the climate (Tab. 1). My point is that these facts, often proposed as alternative explanations to the problem, actually coexist and create a world (and a problem) more complex than suggested by oversimplifying ideologies.

Understanding the data

The IPCC [3] and our own [4] estimates showing the weight of population growth adopt the country as the unit of analysis, while Oxfam [1] and Chancel [2] focus on the income of individuals, independently of where they live. Both strategies have pros and cons.

The sustained global economic growth of the last 30 years (about 3% per year, on average [6]) has disproportionally benefited people in middle-income countries, leading to a general reduction of inequality at the world level (despite a widespread rhetoric arguing the opposite) and to the development of relatively large high-income groups in middle- and low-income countries [7, 8]. This suggests that an excessive focus at the country or regional level may obscure the role that specific individuals play, quite independently of where they live.

A difficulty in doing individual-level analyses is that most existing statistics (including CO2 emissions) are at the country level, which means that they are more accurate and easy to use. In addition, a significant share of the emissions is not linked to the actions of specific individuals, as they derive from the activity of public administration or other large-scale organizations [9]. They hence need to be shared in some way among citizens to allow for individual-level estimations, not always an easy task. In other words, moving from country-level statistics to individual-level estimations implies rather arbitrary choices. This point is especially important and deserves more explanation.

In the framework developed by Chancel, emissions are generated by three different factors: private consumption, public spending, and investments [2]. Direct and indirect emissions generated by private consumption can be without much trouble attributed to the individual who bought and benefited from the good or service under consideration.

Emissions from public spending are instead linked to the provision of infrastructures and services of public interest, such as schools, hospitals or roads. It is not always evident how to attribute the related emissions to individuals, as specific groups differentially benefit from specific infrastructures or services, but a reasonable strategy is to equally split them among all residents in a given country, just as the emissions of, say, commercial flights are usually split among all passengers. This is the baseline strategy used by Chancel, although he also tried alternative splits, which did not drastically change the resulting picture anyway.

The third factor leading to emissions — investments — is the most problematic one. Investments account for a substantial share of rich people’s emissions: about half of the emissions for people in the top 10% group and over 70% for people in the top 1% group. This is not surprising. Although bizarre spending by Hollywood stars or Arab sheikhs may make a good post on social media, there actually are physical limits for consumption, while there are practically no limits for growth in investments. This is a crucial point and deserves a section on its own.

Understanding investments

Investments have two sides, complicating the problem of the attribution of their environmental impact. From the point of view of the investor, they are mainly a way to use money to produce more money. This extra money can then be used for private consumption, and hence can be accounted on the corresponding line of Chancel’s estimations, or re-invested, with emissions that are again problematic to attribute. Why this is problematic becomes clear when adopting the point of view of the actor receiving the invested money, usually a company or the state.

States use this money to provide infrastructure and services to citizens, and these emissions are already attributed to all citizens as consumers of these services. Companies use the invested money to produce goods and services to be sold on the market. It is true that “pure” financial investments are possible, such as rapidly buying and selling shares or financial products on the stock market. Nevertheless, even these financial investments are linked, at the end of the day, to shares of companies producing some good or service for the market.

Money does not come out of nowhere and, at least in the aggregate, the long-term success of financial investments is linked to the market success of real-world activities. However, having success in the market means producing goods and services that ordinary people are willing to buy. An investment may lead to an increased production of cars or smartphones, with related environment impacts, but is only viable as long as there are people willing to buy these items. No buyers, no production, and no environmental impact.

In other words, the investments of rich people often benefit them greatly, but many investments were only viable because billions of new people became customers able to afford cars, smartphones and the multitude of other goods or services offered on world market in the last 30 years or so. This brings us back to the analyses showing the impact of both population and economic growth on emissions [3, 4], and suggests that attributing the main responsibility for climate change to rich people’s investments doesn’t capture the full extent of the problem.

Looking for culprits vs. cooperating

This short explanation should make clear there are both practical and ethical open questions attached to the attribution of environmental costs from both public spending and investments to specific individuals. From the ethical point of view, is it right to attribute 100% of the costs of investments to investors? Or should they also be shared among the people benefiting from the goods and services produced thanks to these investments, similarly to the public spending case?

From a practical point of view, shall we discourage carbon-generating investments, even if the consequences of doing that will be also felt by billions of customers who will no longer be able to afford the goods and services produced by companies no longer receiving sufficient investment money to keep their prices low?

To be clear, I don’t have answers to these questions, nor do I think that it is especially meaningful to find them. There is simply no bullet-proof way to attribute these costs, since, for many human activities, they are the unintended product of collective endeavors that also produce benefits for billions of individuals.

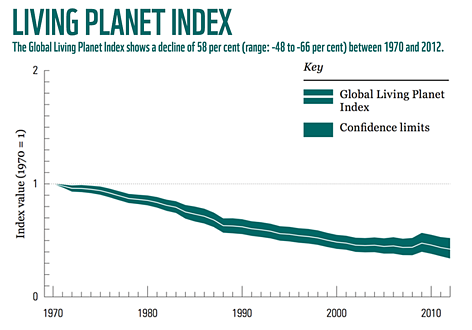

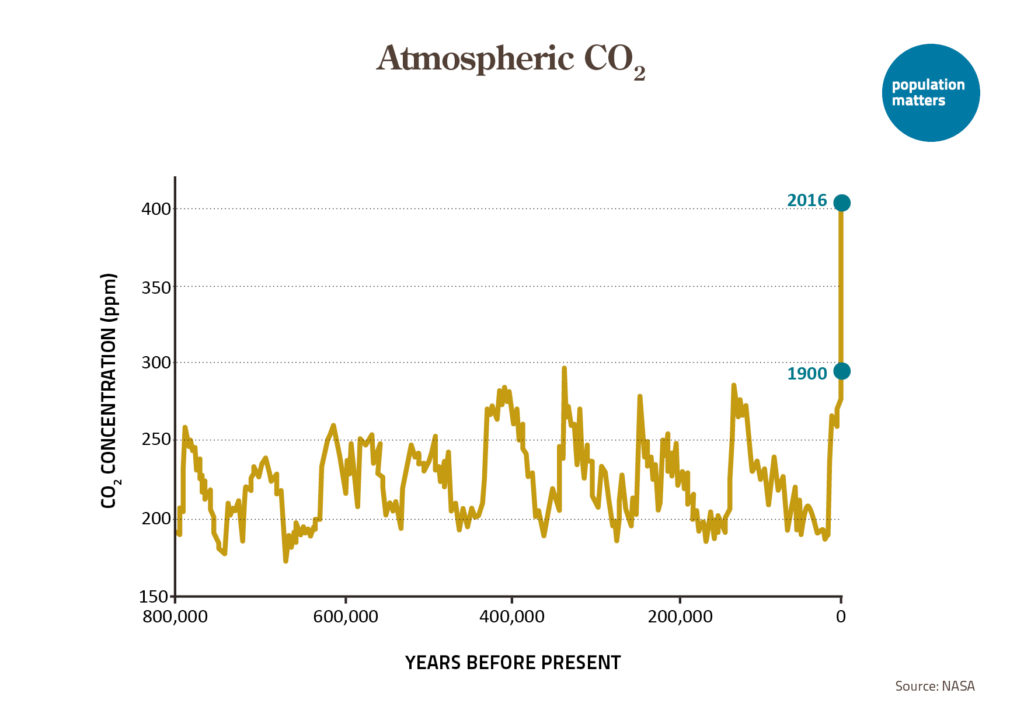

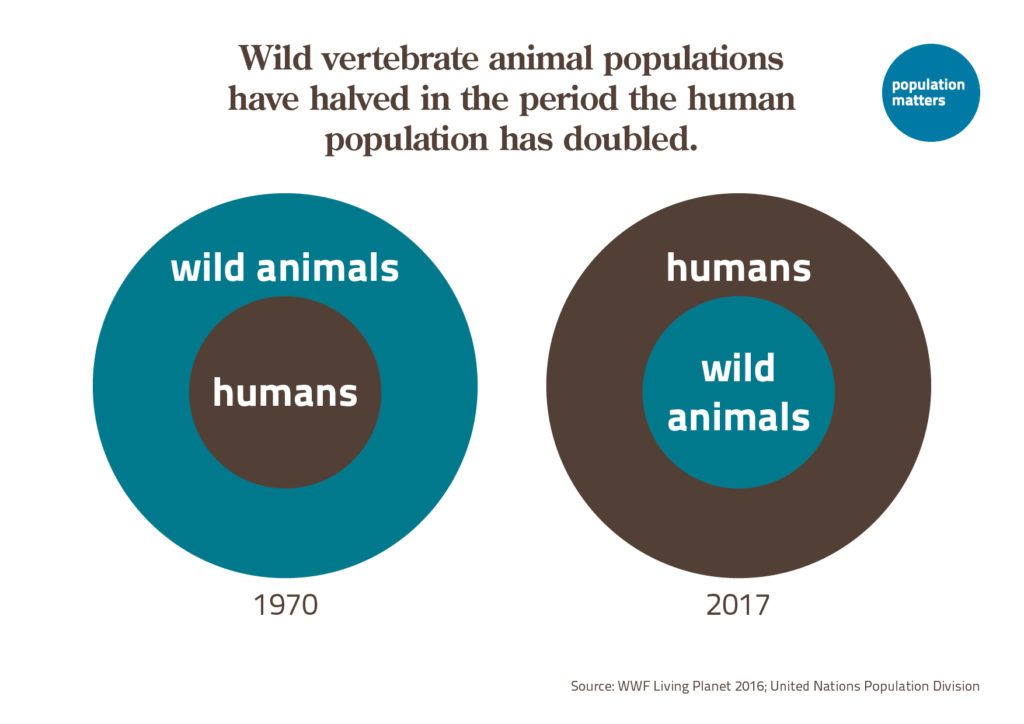

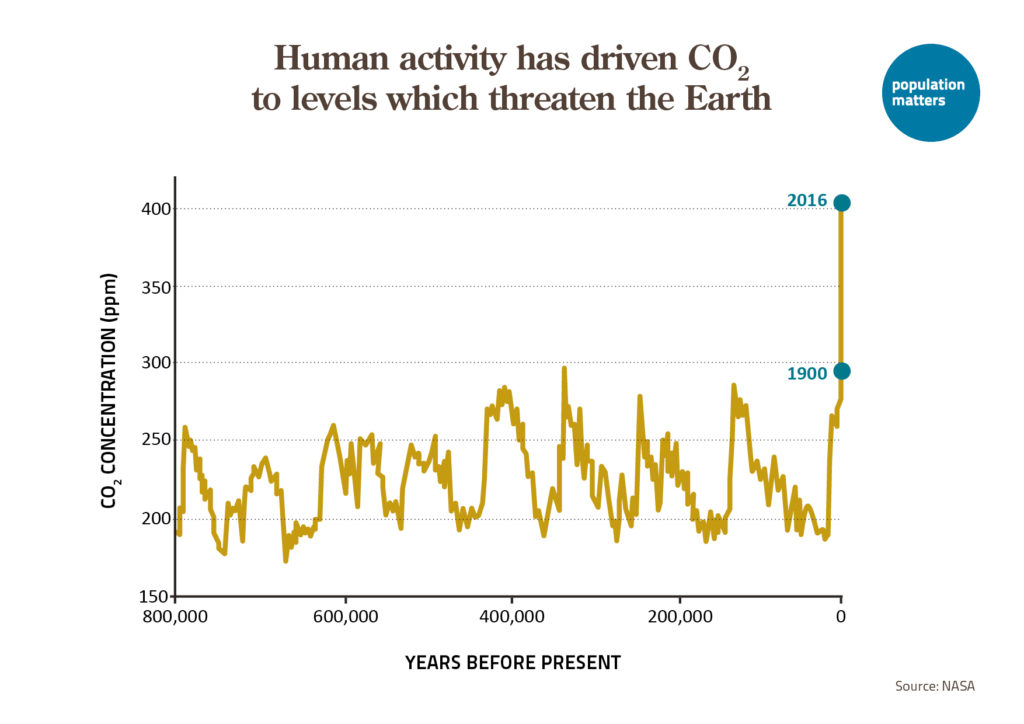

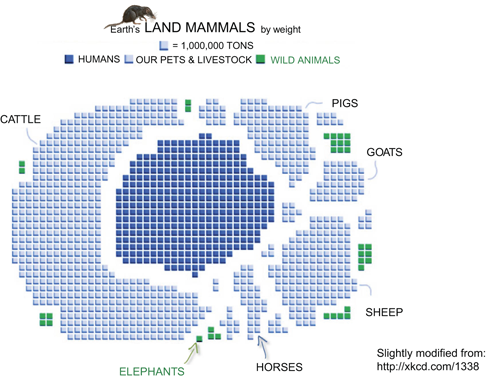

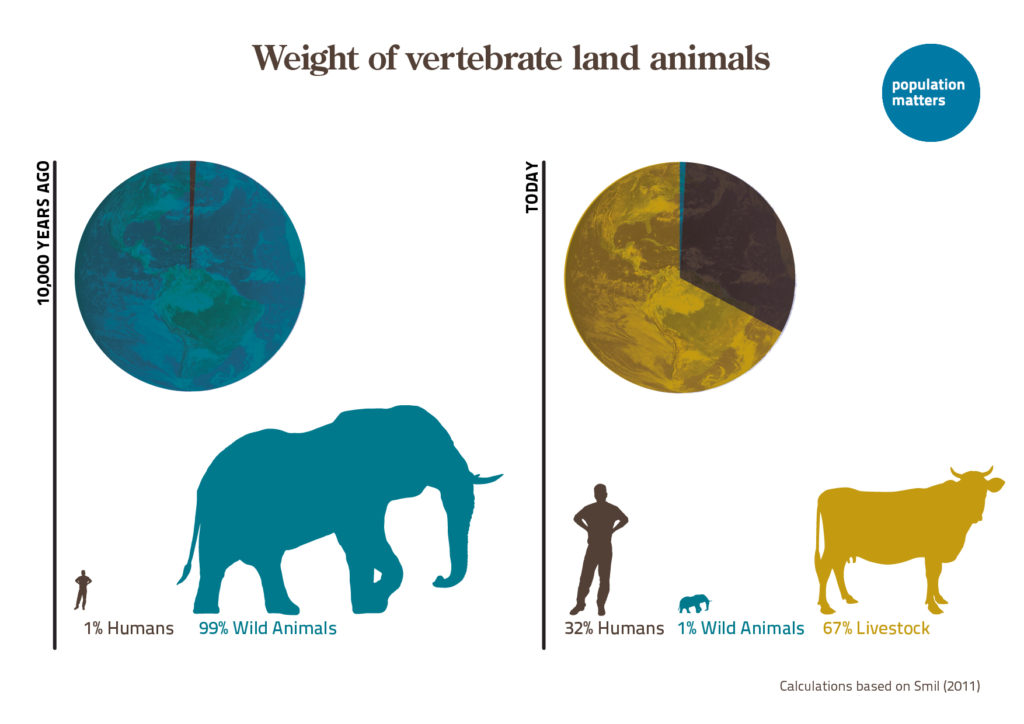

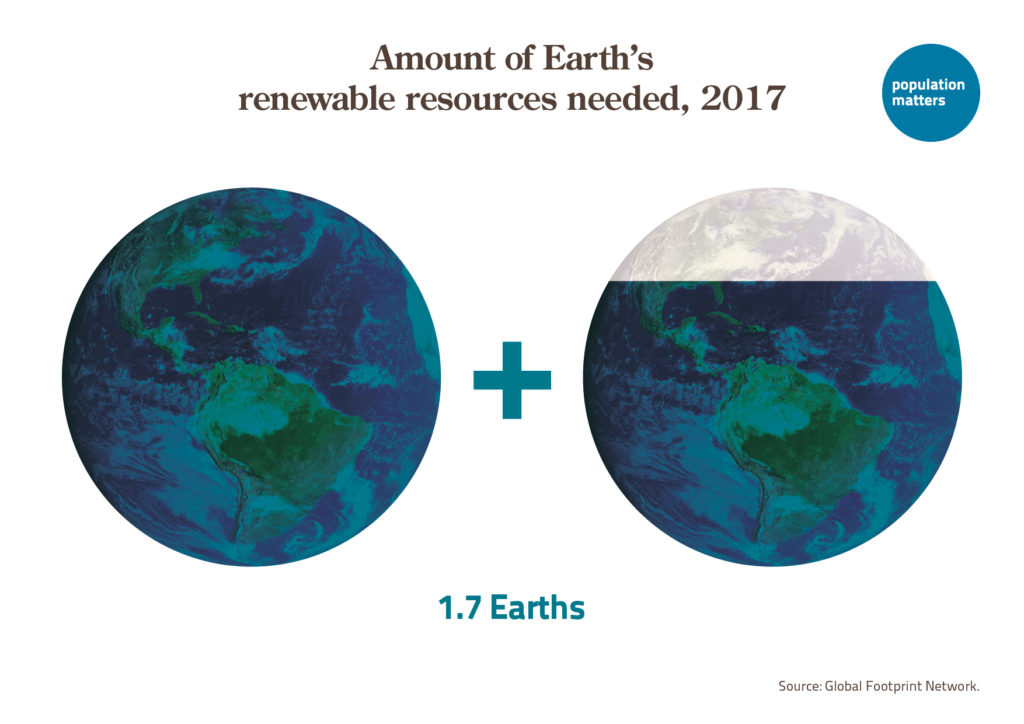

Attributing the responsibility for current environmental problems to specific groups of people — be they American billionaires, 10-kid families in less developed counties, post-communist Chinese consumers, or whomever — looks to me like a meaningless search for an external culprit, if not a scapegoat, which is never us. All this while we try to forget the growing evidence that we are simply too many consuming too much, and that nothing serious has been done about that problem as humanity has charged ever further into ecological overshoot.

There is a further negative side effect of this looking for culprits. Research on shared resource use shows that cooperation and reciprocity are key for the sustainable management of “commons” such as the atmosphere and oceans [10]. Looking for culprits splits people into opposing groups of perpetrators and victims, with roles switching depending on the political position of the commentator. This is something well known to undermine cooperation, making the solution of climate change and other environmental problems even more difficult [11].

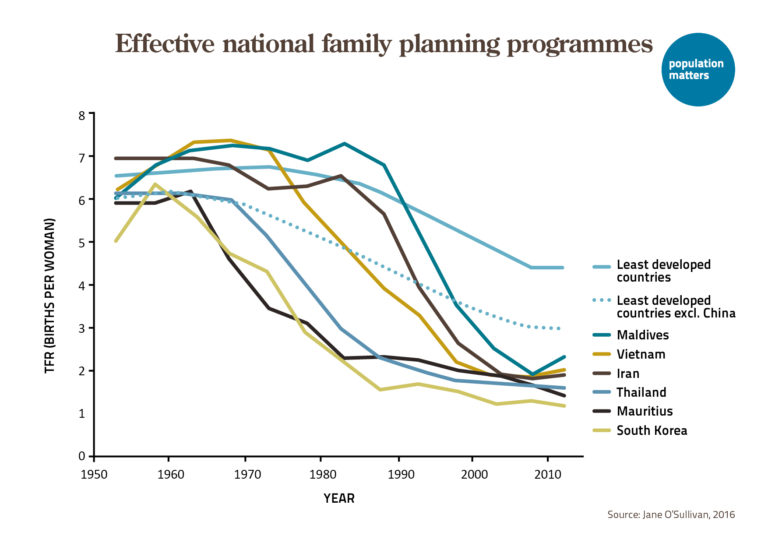

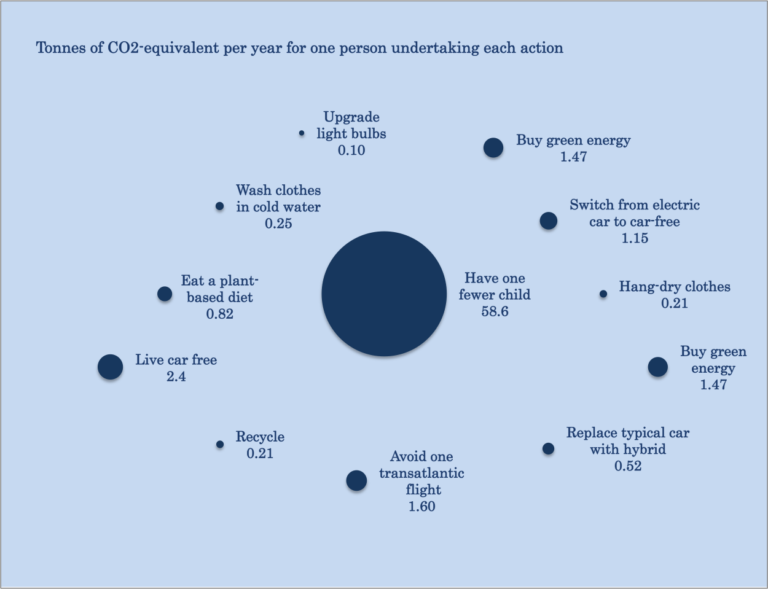

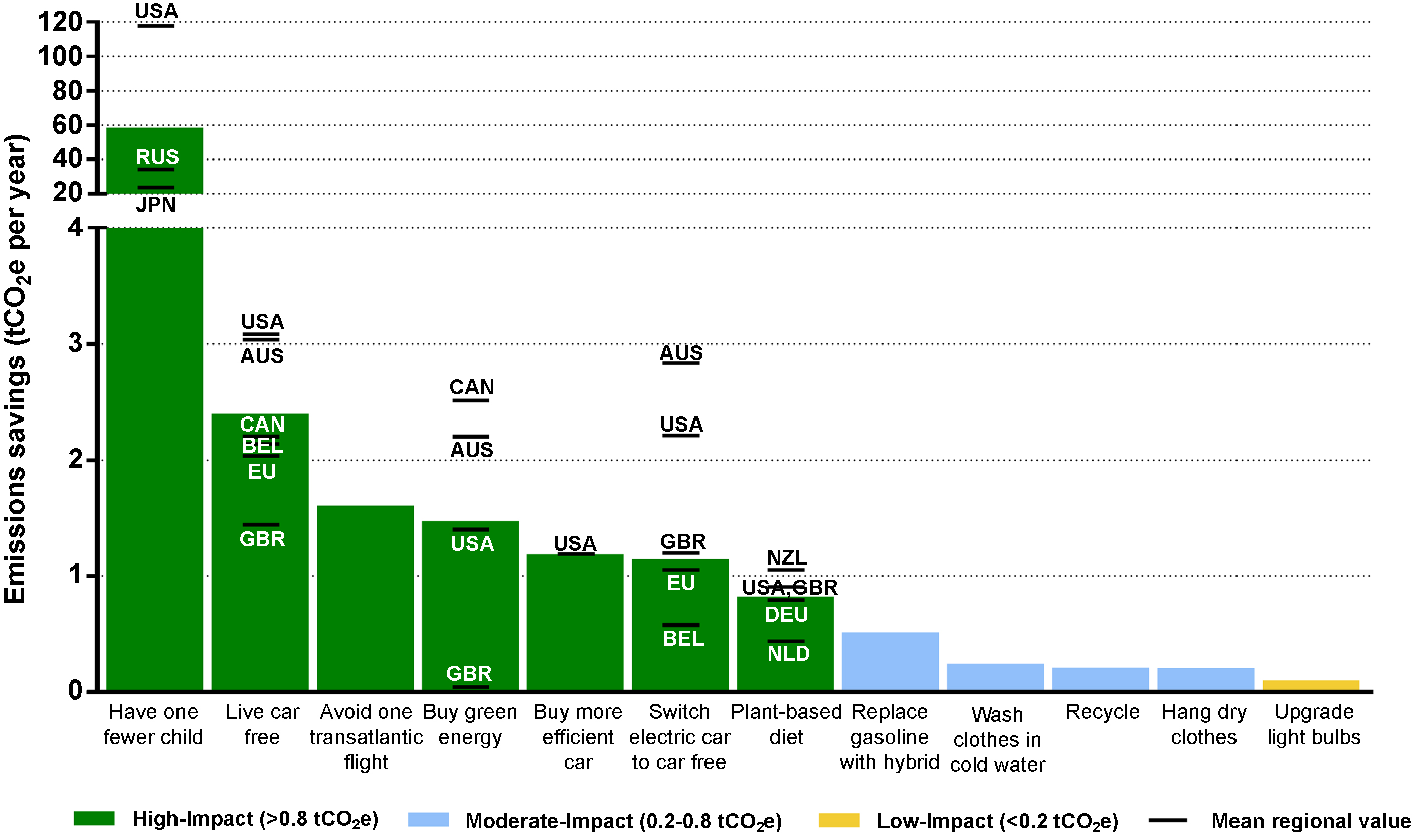

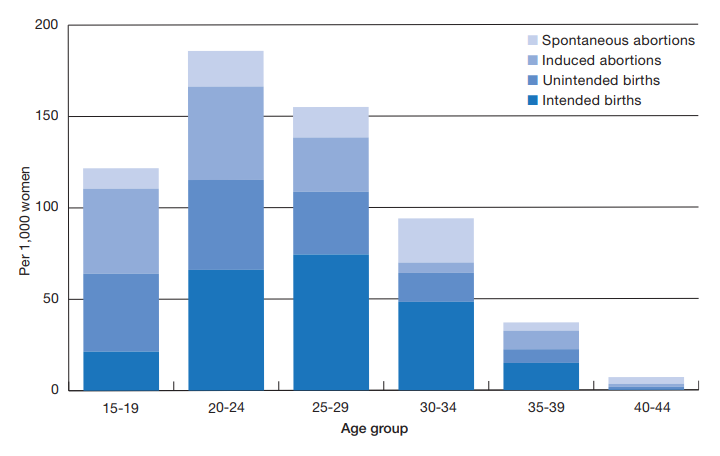

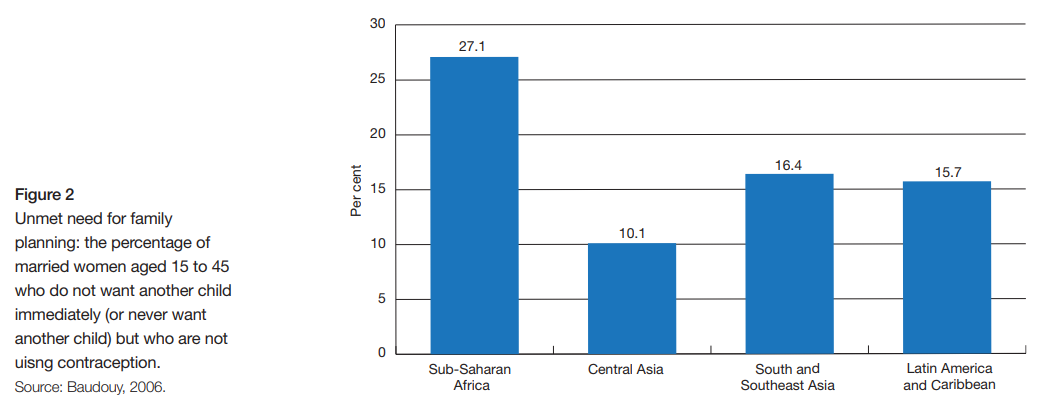

Not facing the evidence that environmental crises are the unintended but actual byproduct of the sheer size of the human population and its constant search for well-being is dangerous. Excess consumption and investments in high-impact activities should be clearly prevented, for instance through appropriate taxation. Further growth of the human population should be discouraged, for instance though increased access to contraception and women’s empowerment.

These and other measures to reduce our environmental impact are not alternatives. Each of them may target a specific issue and studies like the ones presented above have the merit of helping us find the most effective solutions. Nevertheless, this should not degenerate into a detrimental us vs. them fight, nor prevent us from recognizing the responsibility of all. This will only reduce our capacity to cooperate for the collective good.

The famous Walt Kelly cartoon, symbol of the first UN environmental conference in Stockholm in 1972, said, “we have met the enemy and he is us”. Splitting the “us” into smaller groups of culprits and victims won’t help. It just makes finding a solution to the problems we share even more difficult.

Leave a Reply