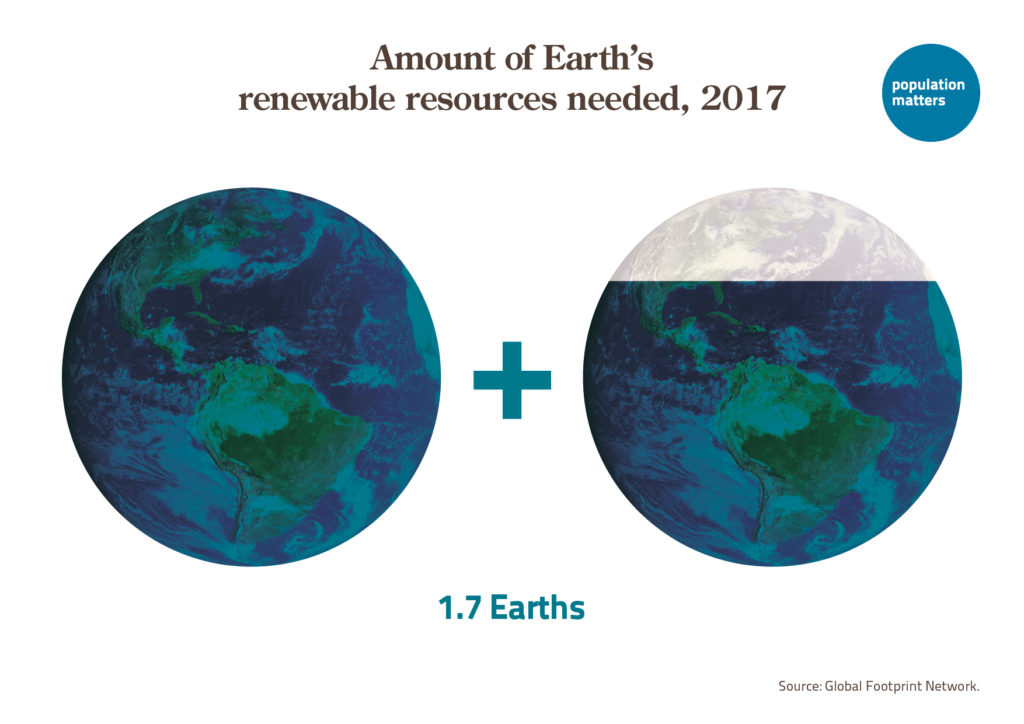

Recently, a TOP blog emphasized the importance of addressing luxurious overconsumption, including the hypocrisy of rich people wanting to be seen as environmentally friendly. Is nature-based tourism merely pandering to this hypocrisy, or can sites with nature-based tourism or ecotourism be beneficial for wildlife in developing countries with increasing populations?

By Oskar Lindvall and the TOP team

Forms of nature-based tourism may increase the motivation and the means to protect natural areas from destructive uses of their natural resources. Ecotourism has been defined as ‘responsible travel to natural areas that conserves the environment, sustains the well-being of the local people, and involves interpretation and education’ (International Ecotourism Society, 2015). Unfortunately, no international certification of ecotourism exists. Some countries have their own ecotourism certificates, but greenwashing seems to be common.

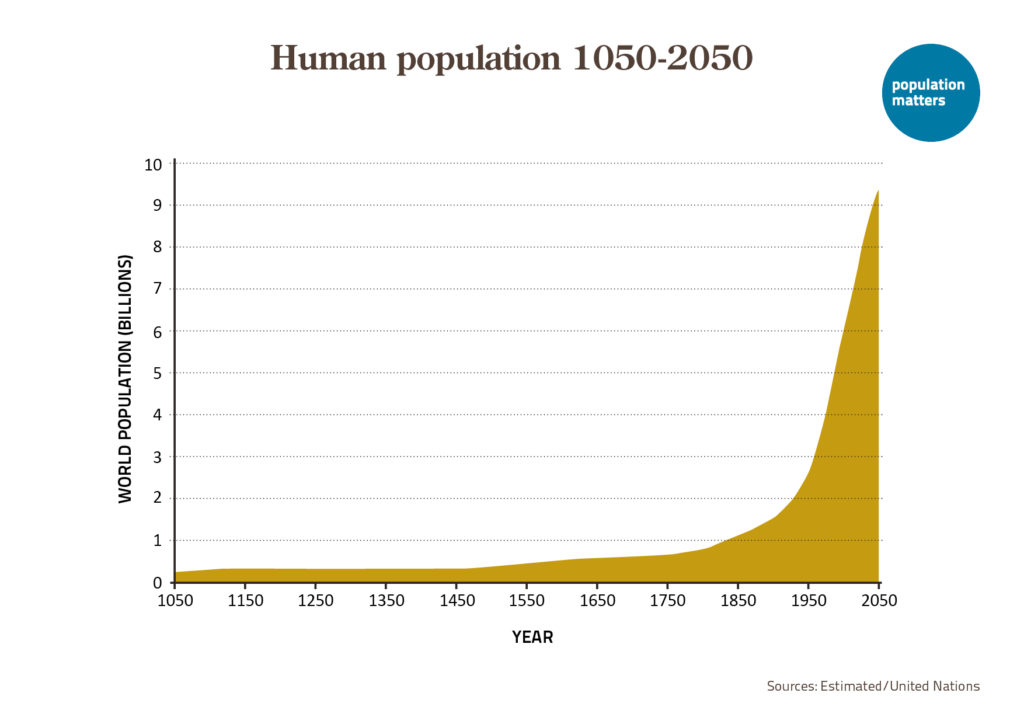

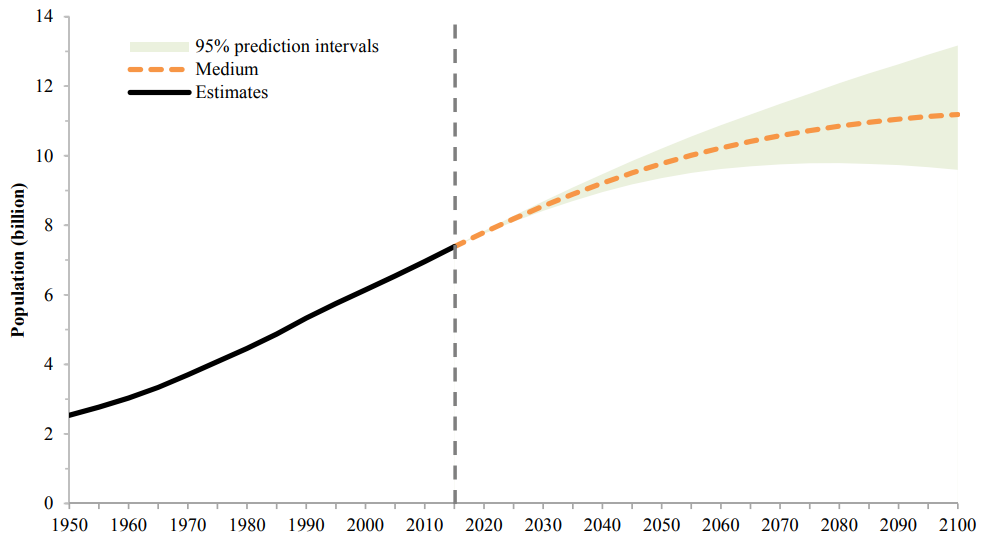

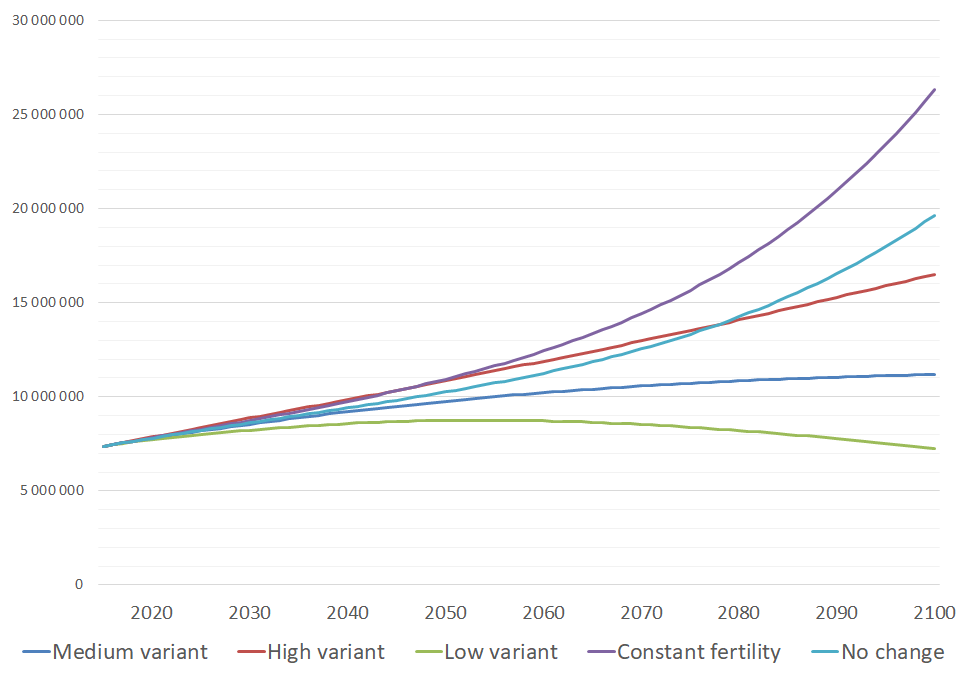

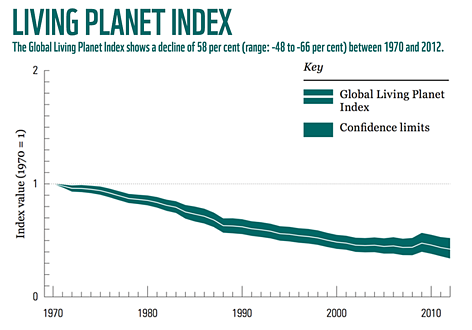

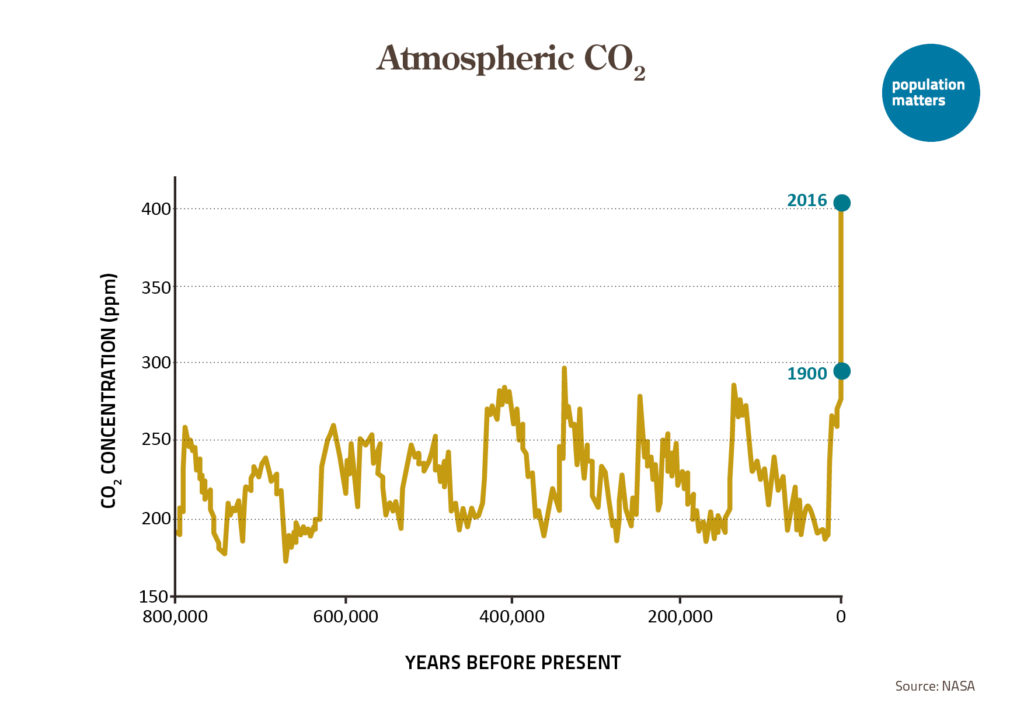

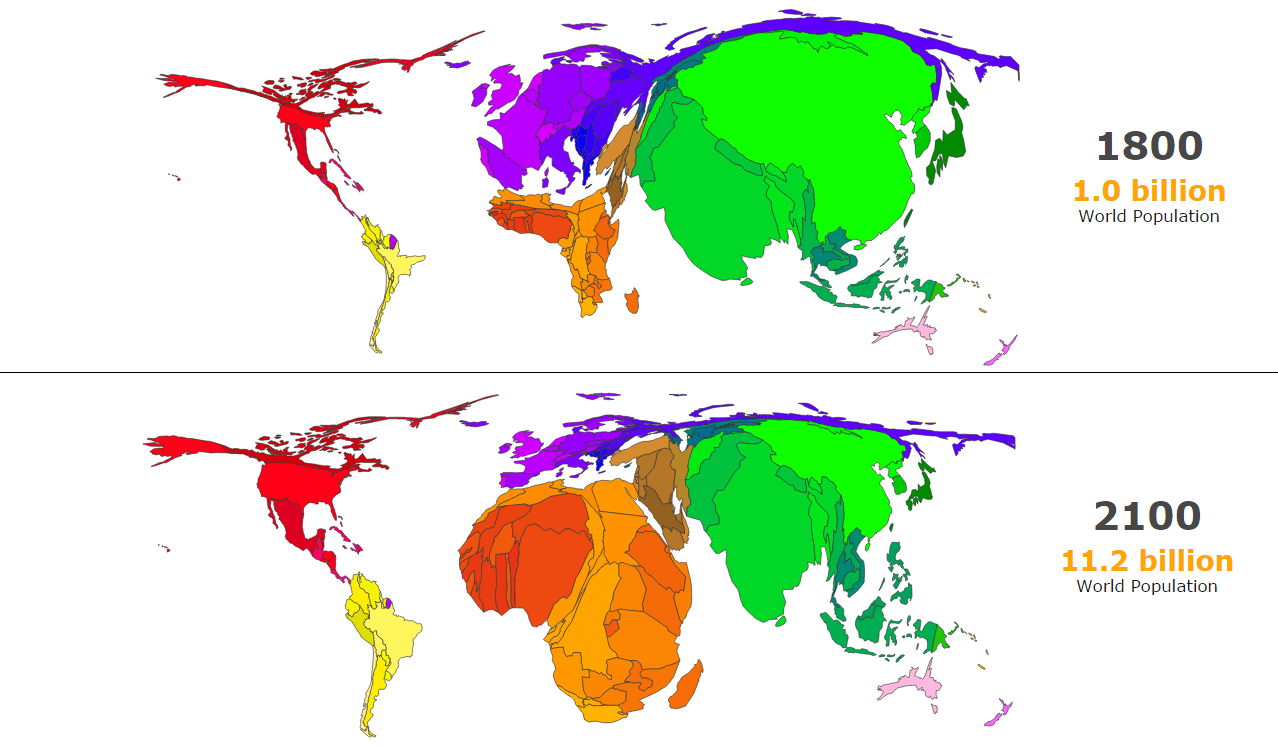

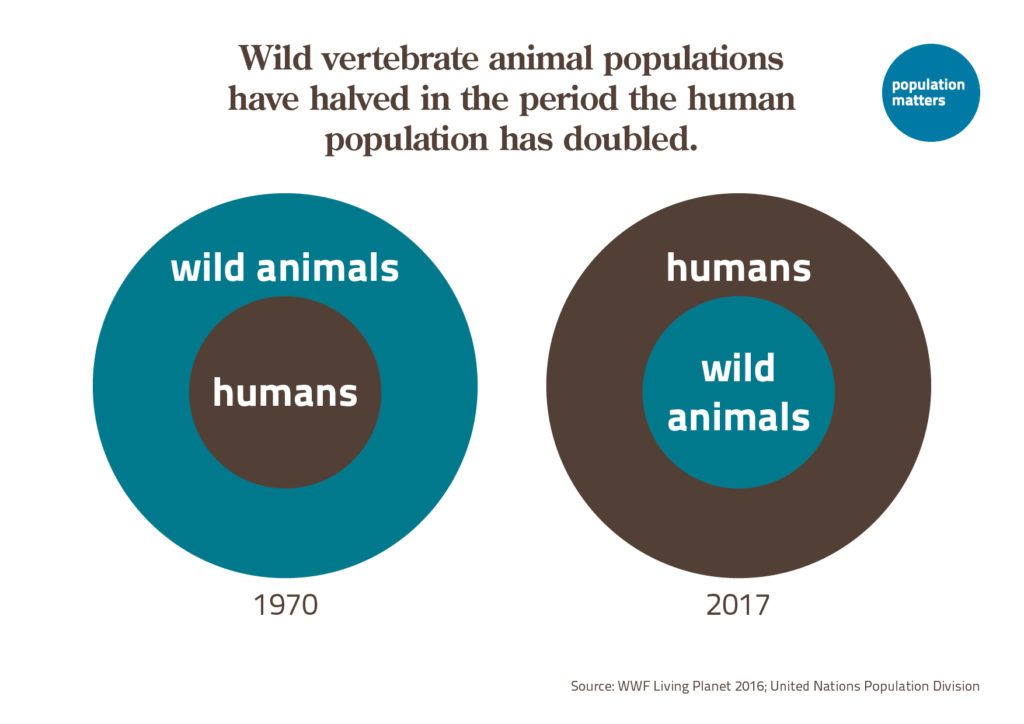

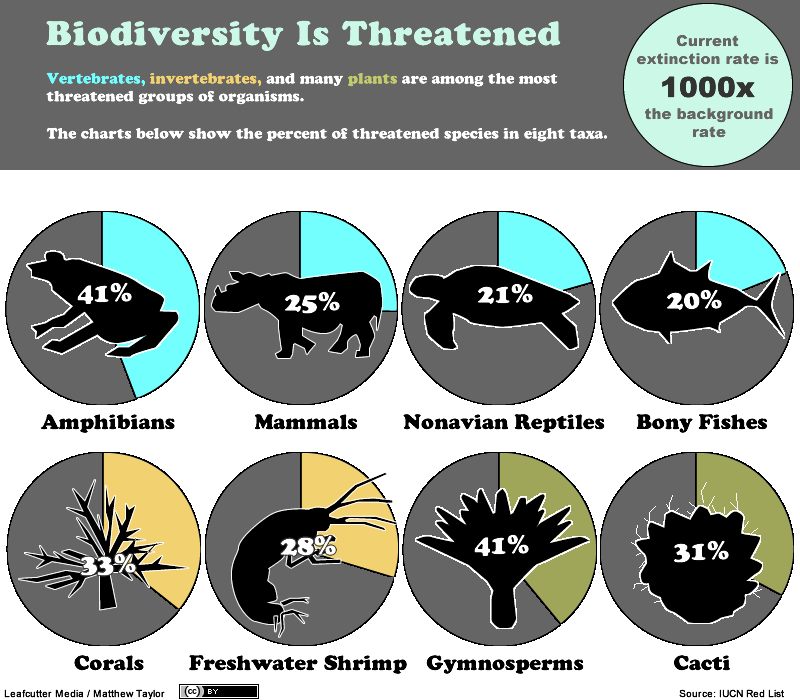

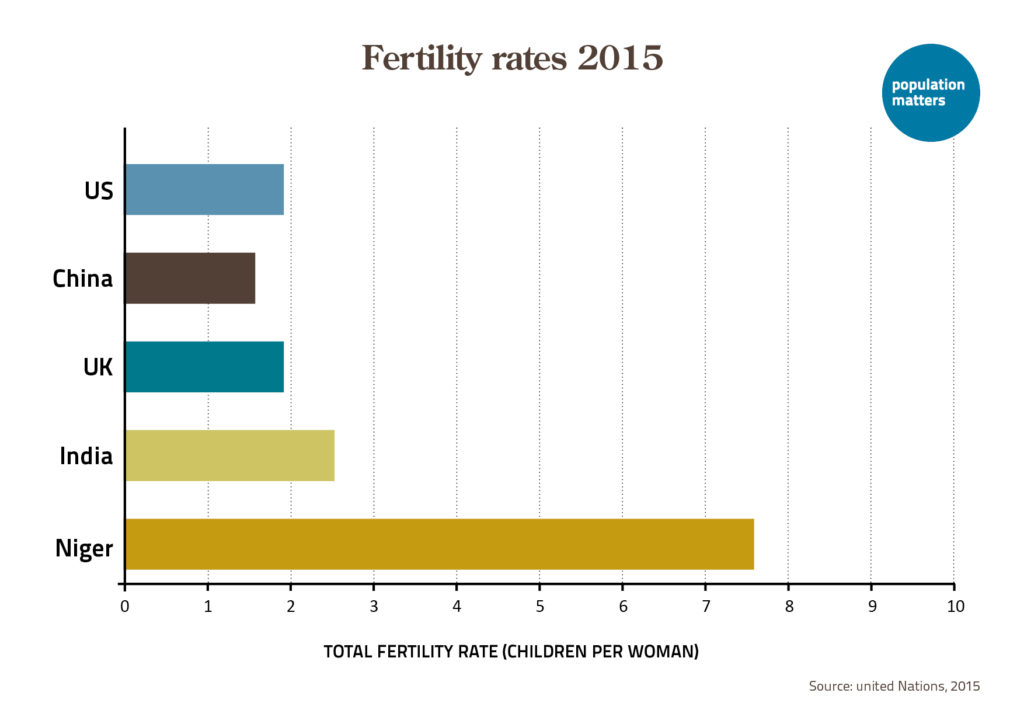

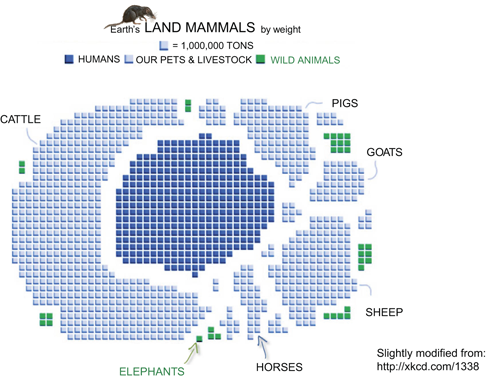

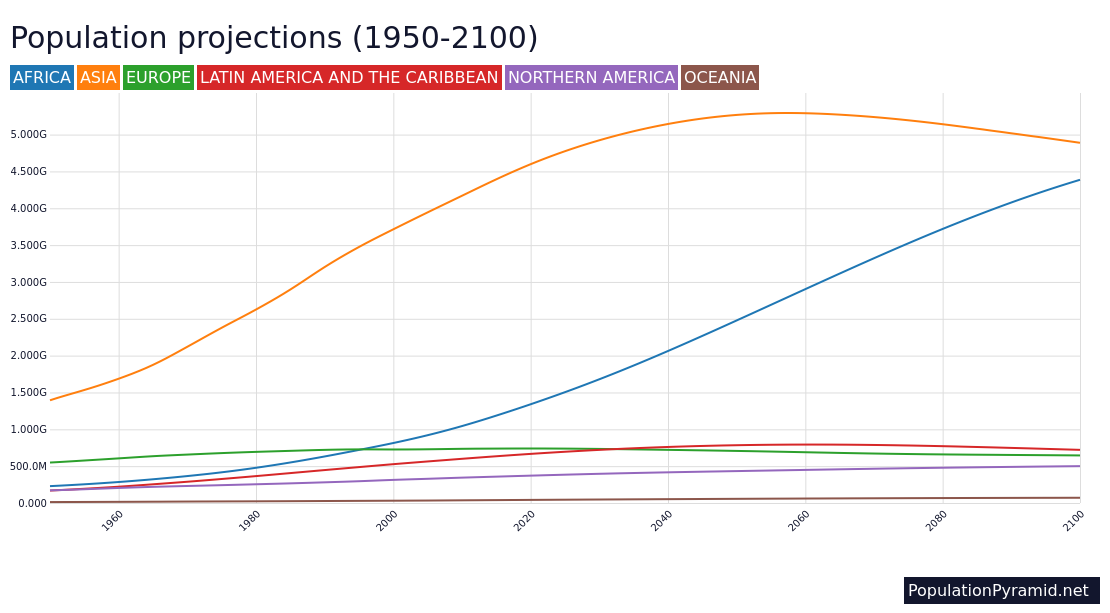

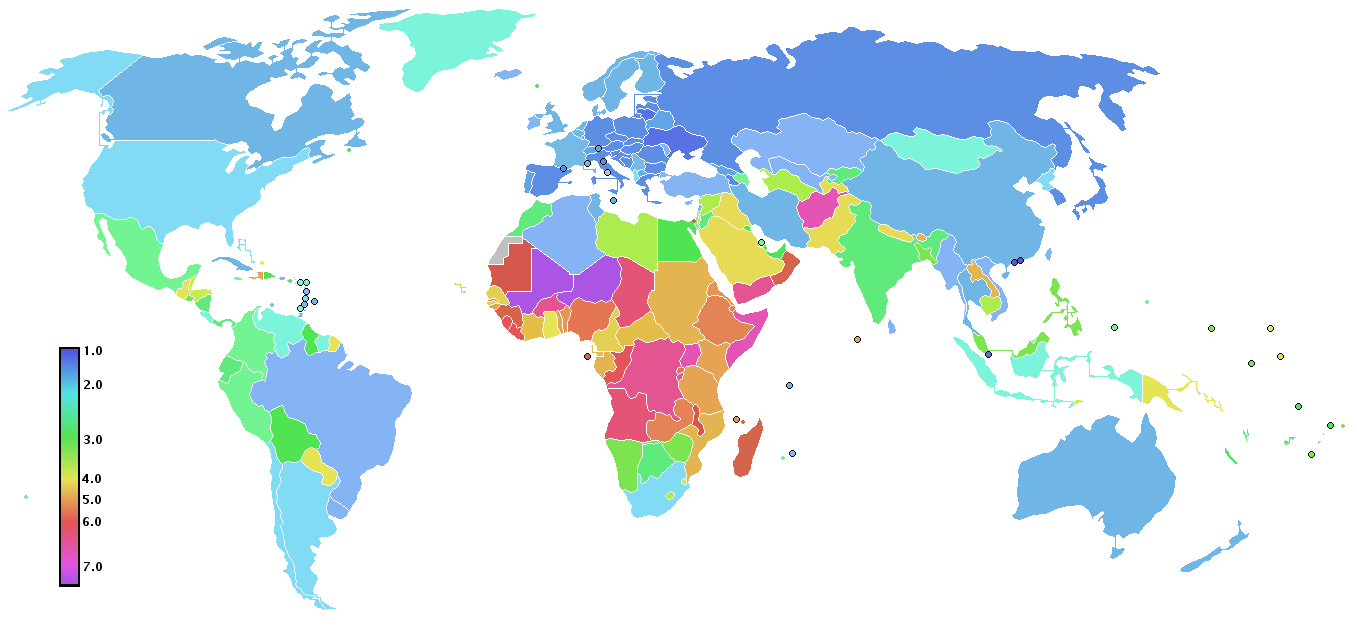

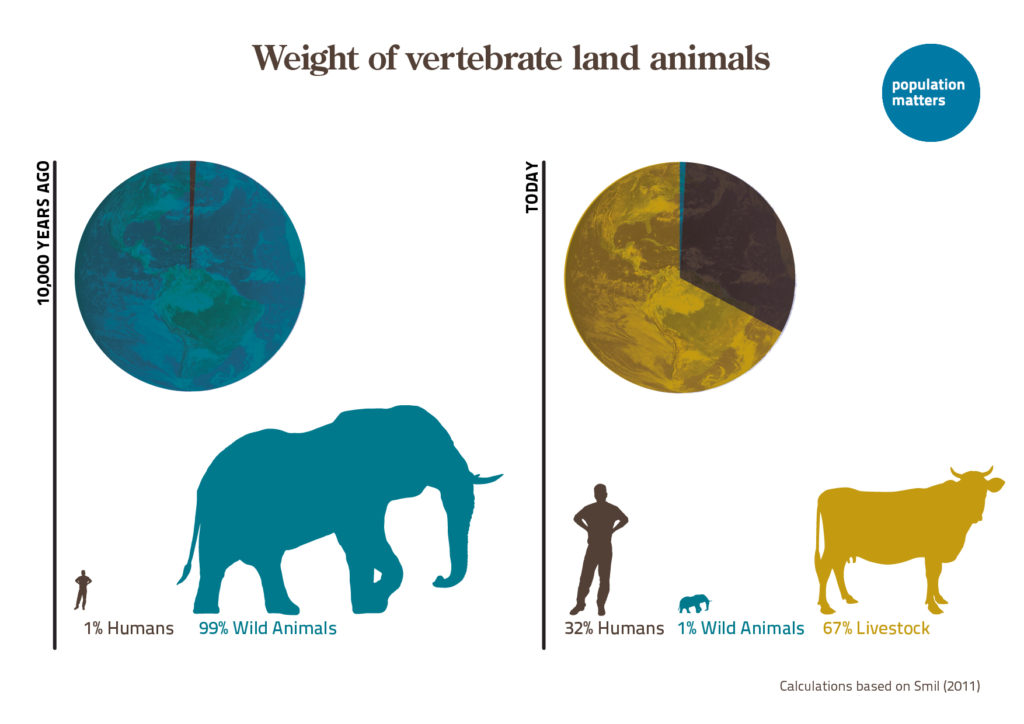

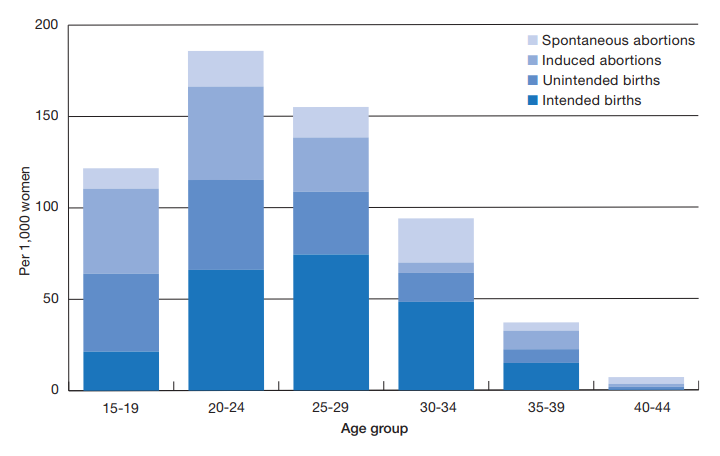

Biodiversity in tropical and other countries near the equator is strongly threatened, even more so in the future due to strong population growth in this region. A recent analysis of population trend data for >71,000 animal species (mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fishes, and insects) shows a widespread global erosion of wildlife populations, with 48% of species undergoing declines and only 3% increasing. For species currently classed by the IUCN Red List as ‘non-threatened’, 33% are declining. Declines tend to concentrate around tropical regions, whereas stability and increases tend to characterize temperate climates.

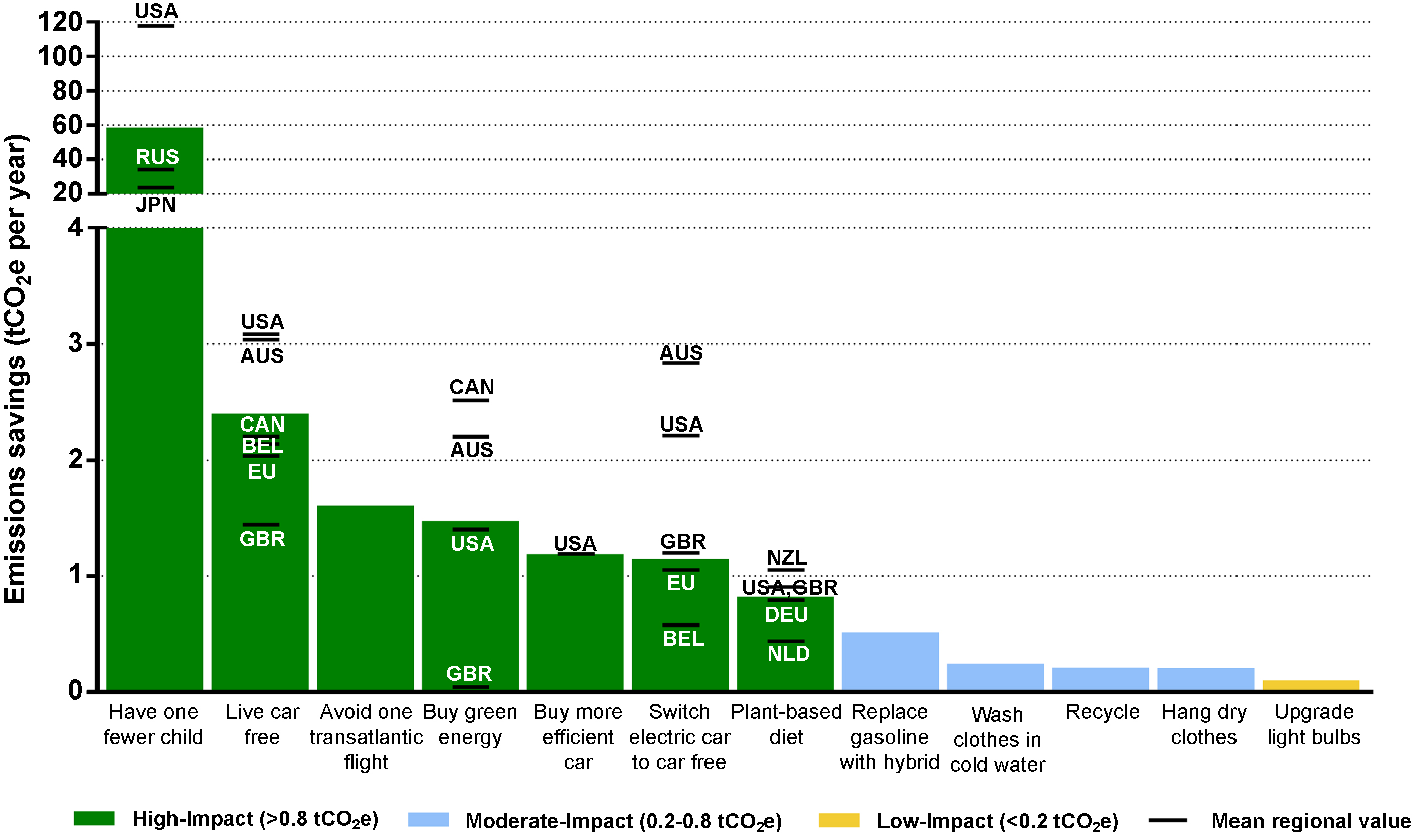

People from developed countries are often (rightly) encouraged to consume less: international flights, and ‘flight shame’, are discussed in relation to climate change. But can tourism to protected areas (PAs) reduce the threats to biodiversity therein (high human density and growth, increasing economic growth)? PAs in developing countries may provide protection against more settlements and economic activity. Protected areas are ranked by the IUCN in six categories, from “strict nature reserves” to “sustainable use of natural resources”, offering sequentially less protection. A global study of many PAs from 2021 compared how well the protection categories correlated with nine factors threatening wildlife, including the degree of human settlements in PAs. Surprisingly, IUCN’s protection level designation was only weakly related to the extent of human settlements there. Settlements were mostly related to travel time to reach the site from the closest major city. This result was true across every continent studied. Thus, establishment of PAs per se might not always be enough to protect valuable nature from human infringement.

Negative and positive effects

A review of the literature on forest protection and nature-based tourism in biodiversity hotspots (mainly located in developing countries) identified factors leading to positive and negative effects of tourism. The review defined the outcomes of the establishment of nature-based tourism as deforestation, forest protection, or forest re-growth. Of 17 case studies, nine resulted in some deforestation. The mechanisms involved were direct or indirect usage of wood for tourism sites, forest clearing to make room for tourism facilities, and economic growth leading to increased population density and more destructive behavior of the local population. In four cases, nature-based tourism directly contributed to protecting the forest. The key aspect of those sites was the combination of nature-based tourism and formal protection, with monitoring and enforcement of regulations (e.g. clear boundaries between tourism areas and conservation areas). Reforestation (re-growth) was an outcome at six of the 17 sites, achieved through tourism income making natural areas potentially more valuable than agriculture. In sum, for about half of the sites the authors found some positive effects of nature-based tourism.

Some studies of individual ecotourism ventures are of special interest. A study of Tambopata in Amazonian Peru compared the economy of different land uses, with apparently encouraging results. Nature-based tourism in this area, rich in wildlife, turned out to be economically more valuable than agriculture, unsustainable logging, or ranching. It is second only to pig farming, which is possible on only a relatively small land area. According to the authors, the study also accounted for the costs of greenhouse gas emissions from traveling back and forth from the Tambopata compared to the benefit of the carbon sink of forest used for tourism.

Botswana is known for expensive nature tourism which may support protected areas and potentially provide income to people locally. A long-term study of the famous Okavango Delta partly confirmed that this is the case. Despite the failure of particular projects there, the author Joseph Mbaiwa concluded that ecotourism has proved to be a tool that can be used to achieve improved livelihoods and conservation.

Both Peru and Botswana have high population growth, but population densities are low compared to countries in Europe, in India, or Japan. Another study compared 15 ecotourism sites and non-ecotourism sites in India, Bhutan, Nepal and China. The study, covering 2000 to 2017, showed that all ecotourism sites suffered from forest loss, and differences between tourism sites and control sites were limited overall. However, differences existed among the countries. Overall, India had lowest loss of forest, but here ecotourism sites seemed to hasten forest loss. China had the largest loss of forest, but in China the sites for ecotourism generally reduced deforestation.

Africa: of special interest for conservation and nature-based tourism

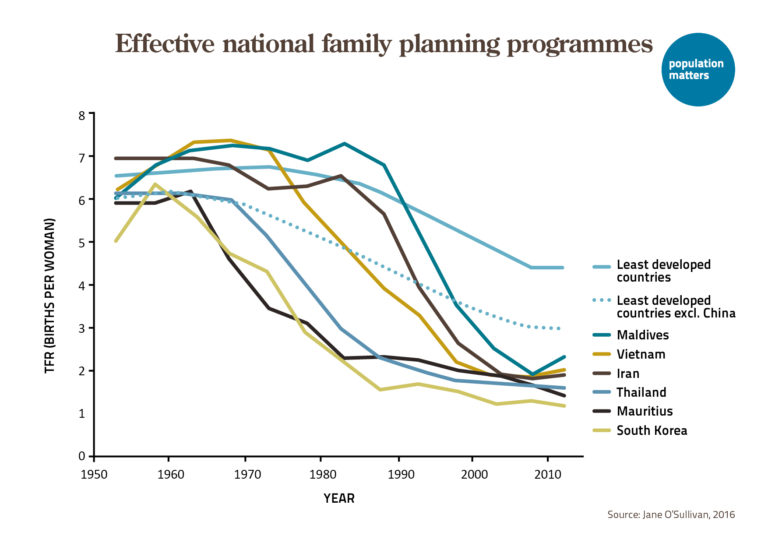

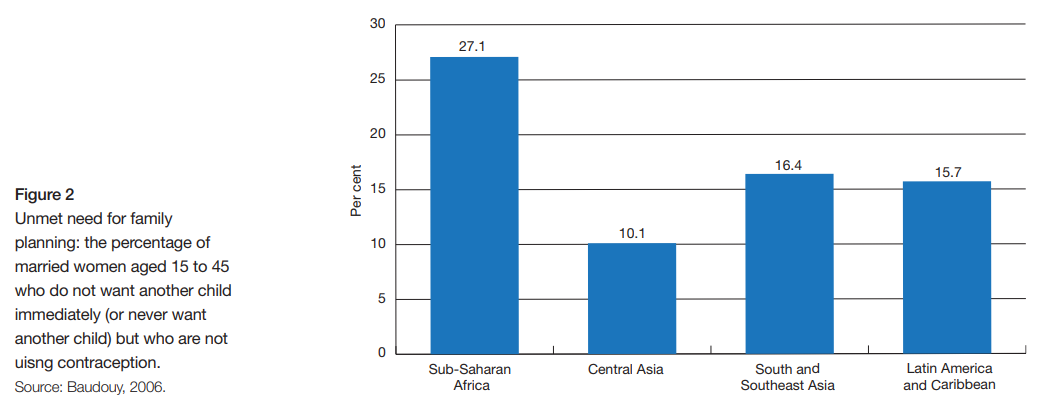

Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is the home of most of the remaining megafauna on Earth and at the same time faces future strong population growth. Here, ecotourism has been centered on the Big Five: elephant, lion, buffalo, leopard, and rhinoceros. But what kind of biodiversity are ecotourists seeking in this region, and where do they go? A detailed study recently analyzed annual tourist visits, the occurrence of nine mammals, bird species richness, forest cover, national wealth, local human population and accessibility for 164 PAs in SSA. The authors concluded that tourist preferences extend beyond the Big Five to also include bird diversity, that ecotourism may be well suited to conserve bird diversity, lion, cheetah, black and white rhinoceros, African wild dog and giraffe species, and that visitors seem to prefer wealthy countries. However, few ecotourists visited forested areas, apparently due to the difficulty and risk in reaching SSA’s remnant forests which are often in remote or politically unstable areas, while the rewards are less certain as it is harder to spot birds and other species in forests. Strictly protected areas are thus clearly needed – although difficult to enforce in Africa under future strong population growth. Like other ecotourism researchers, the authors did not discuss human population growth or cite the positive role of family planning in the potential stabilization of human populations in SSA.

Russia: unusual protection

Russia is not a developing but an economically unequal country, almost dictatorship, with weak tourism, yet interesting. Most readers are probably unaware of Zapovedniks, a network of large areas in Russia established from around 1895, only for wildlife and science. Visitors were not allowed, but small conservation teams worked at the sites and survived two World Wars under hard conditions. The communists during the Soviet Union era had apparently little interest in tourism in the Zapovedniks, and those who argued for wildlife and science managed to defend the areas. Feliks Shtilmark describes the history of the areas (1895 – 1995) in this book. If you wish to view large fantastic natural areas, take a look at the photos on this Wikipedia page, showing about 100 Zapovedniks distributed all over the country. For more information about nature in this odd but large country, see this site.

The Covid-19 quasi-experiment

The Covid-19 pandemic provided a quasi-experimental situation, in which tourism greatly diminished. Already in the summer of 2020 there were reports of decreasing tourism leading to a chance for nature to revive itself (due to less disturbance from tourists) but also increased poaching in many PAs. Surveillance of the areas declined, partly due to decreased tourism which led to a lack of funding for protection.

A study in Morocco from 2020 reported that, during the Covid-19 lockdown, poaching and wildlife trafficking increased in the PAs. A study of the implications for wildlife in Zimbabwe also found increased poaching during the lockdown, when no tourists were allowed in any PA in the country. The authors describe the security of PAs during full lockdown, partial lockdown, and no lockdown (imposed during different periods). They show that the protection of the PAs was financed during the pandemic, despite a sharp decline in tourism income. This was thanks to financial reserves and increased help from conservation partners. However, despite formal protection, such as guards in place, poaching still increased during lockdown. This could reflect the economic hardship in local communities deprived of income from tourism. Alternatively, it could indicate that tourism activities not only tend to disturb ecological values, but also illegal activities threatening those values. One should bear in mind that even though research points to increased poaching in PAs which were financed by nature-based tourism, this might not only be due to the decreasing nature-based tourism.

Conclusions and points to consider

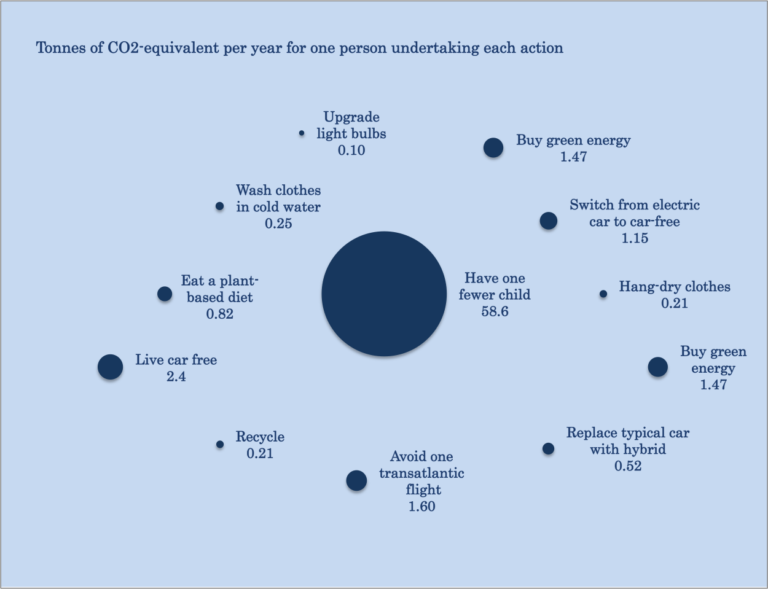

Clearly, the outcomes of nature-based tourism differ, in complex ways, and it is hard to predict its fate before establishment. While the outcome, if combined with some strict protection measures, can be a net-positive in developing countries with large and growing populations, several problems remain. First, the negative environmental externalities associated with nature-based tourism include air-travel, ‘footprints’ from tourism infrastructure, and local deforestation. Overall, nature-based tourism is far from a certain positive outcome. PAs with strict protection are much needed.

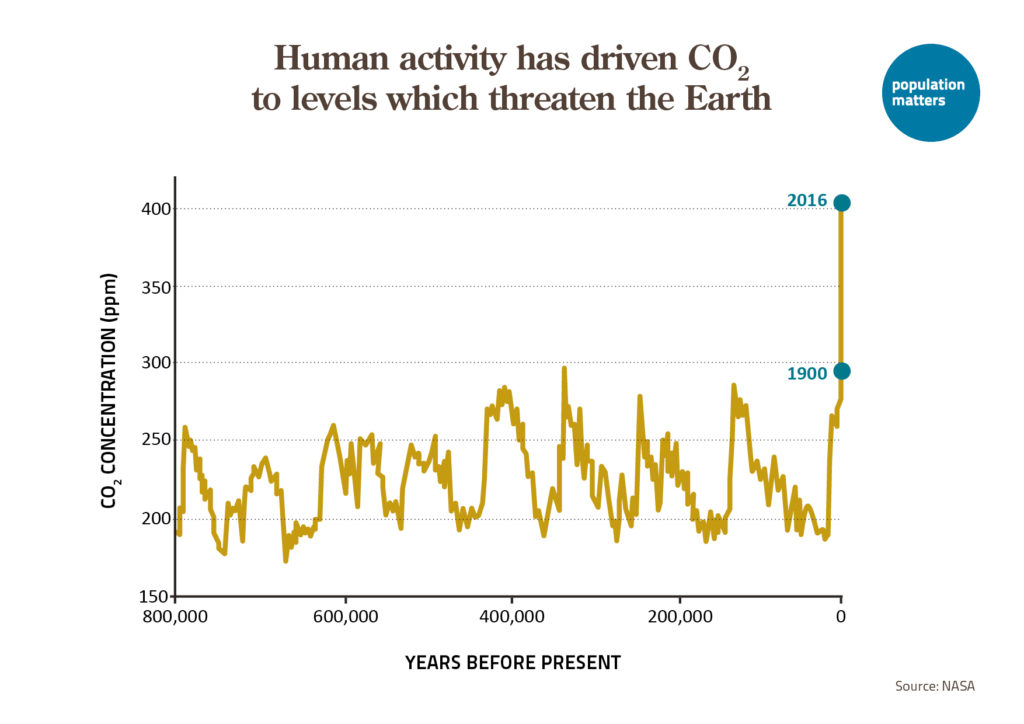

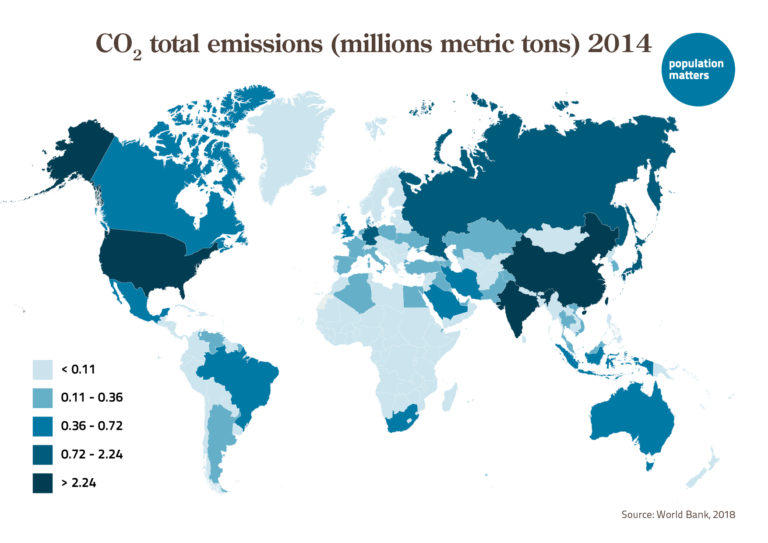

Second, what are the impacts of nature-based tourism on lifestyle ethics? Overconsumption and overpopulation are the main drivers of environmental destruction and species extinctions. Nature-based tourism largely depends on rich, or relatively rich, consumers. Do their experiences of wilderness contribute to a stronger conservation ethic in the wider community at home, or at tourist sites? Are there ways to extend these experiences to the wider public, without “loving to death” natural areas under high visitor pressures?

The mental image of nature-based tourism in developing countries mostly being for “well-offs” is becoming less true year by year, as the middle class in these countries grows and gets wealthier. The growth of domestic tourism changes the consumption patterns. In China, domestic tourism was growing rapidly before the Covid-19 pandemic, with an overwhelming share of the visitors to Chinese parks. In India, where wildlife is threatened by the purchasing power of a growing middle class and encroachment by a rapidly growing population, nature-based tourism has potential to help preservation efforts. Also here, domestic tourism is growing rapidly in importance. In South Africa, where nature-based tourism has long played an important role for preservation efforts and local economies, nature-based tourism providers are increasingly dependent on domestic tourism. In other African countries such as Tanzania and poor countries elsewhere, the importance of domestic visitors is marginal at best. For PAs in these countries, negative externalities such as international travel are problematic, yet probably still needed: if the population lacks the means to form strong domestic nature-based tourism, income from other tourism might help sustain livelihoods and hopefully support protected areas under the threat of growing populations.

Leave a Reply